The last 15 years have seen an unprecedented expansion of surveillance, mostly via massive electronic monitoring. This has happened behind closed doors and without the consent of the American people. The intelligence agencies have repeatedly gone way beyond the scope of the already-questionably legal powers afforded to them and lied to (or at least mislead) congressional investigation panels. See: How to Tell When the N.S.A. is lying and The Government's Word Games When Talking About NSA Domestic Spying among many other articles. Few, if any of these spy programs have ever come before a public court. The single exception being a case before the District Court in Boston at the end of 2016.

A new decision would allow the extension of these powers to recording any telephone call without oversight and keeping these recording up to 5 years. (The relevant case is FISA Court of Review docket 16-01.)

This is wrong.

We have the chance to challenge these unconstitutional and intrusive programs - on their own home turf. I and Attorneys Michael and John Walsh are posing such a challenge. In late November, we filed a legal brief (petition for certiorari) with the United States Supreme Court.

Background

Legal

However, before we get into the details of that, it's necessary to give a quick legal primer. All Foreign Intelligence matters (which includes anything terror-related) are put before a special court - the FISC (Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, also known as the FISA Court). This court is secret - by default all materials are classified and the defendants don't even know they need to defend themselves. In fact the court gets to decide if the intelligence agencies will even have any opposition. The single exception is if the case involves "a novel or significant interpretation of the law", in which case the intelligence agencies must be opposed.

Decisions from FISC requiring review go to the Foreign Intelligence Court of Review, abbreviated either FICOR or FISCR. Obviously when the intelligence agencies are often unopposed, this happens only rarely. In fact, in 38 years of existence, FICOR has issued 3 decisions.

From FICOR, decisions go directly to the Supreme Court of the United States. This has not happened in the history of FICOR, though we certainly hope to make history by being the first case to do so.

The decision that we are challenging is a "certified question of law" from FICOR - basically, someone wanted the court to write a binding order saying they were operating within the bounds of the law. The intelligence agencies use Pen Registers and Tap/Trace devices (which I will simply be calling pen registers) to keep track of which numbers users make calls to and receive calls from. From a legal perspective, pen registers are a “must issue” - once an intelligence agent requests a pen register, a judge must grant it, unless the request is clearly illegal. The request for it is simply a courtesy.

Technical

Whenever a button on a telephone is pressed, a specific pair of tones is sent. These are called DTMF (Dual-Tone Multi-Frequency) tones and have been in use in the telephone network since the late 1960s. DTMF can be used to convey DRAS (Dialing, Routing, Addressing and Signaling) information (also known as telephone metadata), as well as call “contents” - anything that isn't telephone metadata, like passwords, pins, credit card numbers, etc. When used to convey telephone metadata, DTMF is not protected information. After all, the user is voluntarily sharing that information with someone (the telephone company), without expectation of privacy. However, DTMF is protected by the fourth amendment when used to convey content.

Normally, a very clear line is drawn between content and non-content. This is often called “The Fourth Amendment Veil”. Usually the separation provided by the veil is very clear. For example, in most calls DTMF is only used until the call connects – then everything is content.

However, our intelligence agencies are worried they might miss something if they don't capture the telephone metadata that is embedded in calls. The argument that they are allowed this information is likely valid (so long as no protected information is captured), but the decision certifying this is based on legal fallacy and technical inaccuracy. It is this decision we are challenging.

FISCR's Decision

The decision allows pen registers to be used to capture and store the entirety of calls – content and all. The intelligence agencies contend that there is no way to separate out the dialed digits that are telephone metadata from those that are content in real time. They say that they therefore will need to collect the entire entire call and sort out what is content and what isn't at an unspecified later date.

The court concurred with the intelligence agencies and used two reasons to justify the decision – a foreign intelligence exception to the 4th amendment and a unique interpretation of a “savings clause” as allowing the capture (but not use) of protected information.

Both prongs of this decision are wrong. The FISA courts were created in 1978 to eliminate the foreign intelligence exception to the fourth amendment. The court is using the reason for its existence to justify its decisions - an argument so circular it would be amusing if it didn't involve massive privacy violations. Since FISA was created, every court – including the Supreme Court – has refused to recognize the existence of any sort of foreign intelligence exception, further proving that this justification is incorrect.

Second, the savings clause. The FICOR decision says that the collection of call contents is okay because it is “incidental” and cannot be used in court. Unfortunately for FICOR, this interpretation has previously been examined and discarded in “United States v. United States District Court” (otherwise known as the Keith case). Further, in the legal context, incidentally collecting information requires that the information was collected by accident – clearly not what FICOR is proposing here.

Additionally, the law requires that “minimization procedures” be used to minimize the inadvertent capture of unrelated data. FICOR did not include any requirement for minimization whatsoever, opting instead to give full authority for the intelligence agencies to record and keep the entirety of all calls.

FICOR didn't even get the technical part of this correct. It is eminently possible to separate content digits from telephone metadata digits in real time. In order to prove this, I wrote a program called CCAD – the Call Contents Automatic Differentiator (source code and technical paper) which can perform this separation in better than real time. CCAD is a proof of concept program that uses no new or unique algorithm (in fact, the core algorithm was first published in 1958 – making it almost twice as old as I am) to identify valid phone numbers in the US and Canada.

CCAD

CCAD operates in better than real-time. In fact, tests showed that it was able to process an average of 9 minutes of audio per second per computing core. It is worth noting that no optimization whatsoever has been done to CCAD – it likely could operate significantly more quickly. Additionally some work is required to have CCAD operate with international telephone numbers. Alas, this is the nature of a proof of concept program.

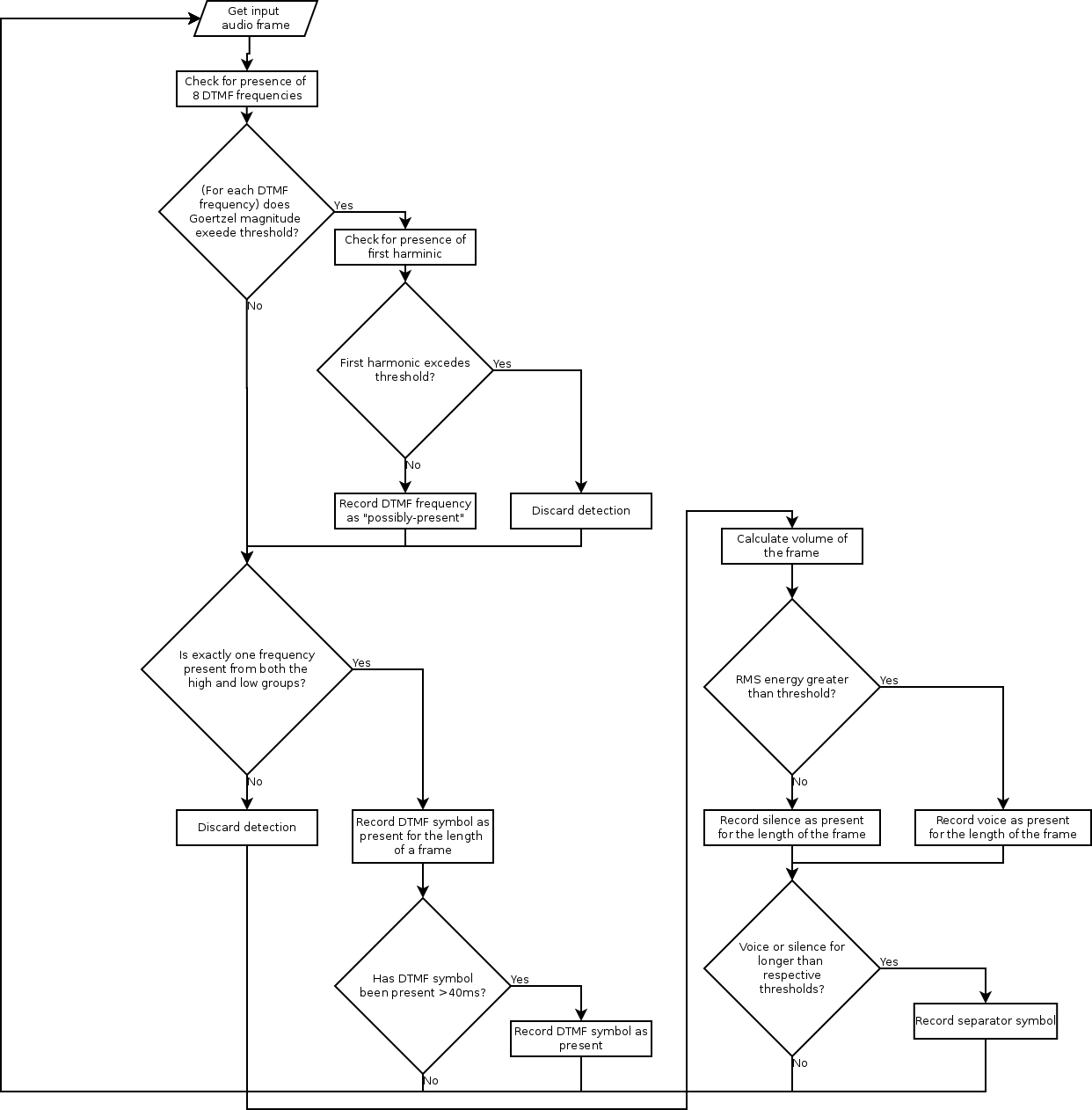

CCAD operates by creating and examining “signal streams”, which represent the relevant contents of the call. A signal stream includes any dialed digits as well as special symbols to represent voice or long silences. It takes short sections of audio (~10ms) and examines them using an algorithm called Goertzel's Algorithm. Goertzel's Algorithm is used to determine if specific frequency “bins” are present in an audio sample and is one of the more basic algorithms in Digital Signals Processing (DSP). CCAD applies it to determine if a sample consists of DTMF, voice or silence. If a DTMF tone is detected (and has been on for the requisite amount of time), it is added to the symbol stream. Second, if voice is present and has been for the last second, a separator symbol (CCAD uses the period) is added to the signal stream. Finally, if the sample is silent and has been for 10 seconds, a separator symbol is also added to the signal stream. For CCAD's purposes, any voice frames are also counted towards the length of time the input audio has been silent.

CCAD Stage 1 Operation (click to enlarge)

CCAD Stage 1 Operation (click to enlarge)

After a signal stream is generated (though there is no reason it couldn't be done concurrently), CCAD looks at it to determine if there are any valid phone numbers. In short, it breaks the stream on each separator symbol and examines each part to see if it is 10 or 11 digits long (optionally followed by an octothorp/pound sign). If 11 digits long, it has to start with a 1. It then checks that the first digit (after the one, if 11 digits) is not a 1 or a 0 – North American area codes never start with 1 or 0. If it passes all these tests, CCAD presumes it to be a valid phone number and marks it as such.

Despite it's rudimentary nature, CCAD operates quite well. Tested on over 400 YEARS of computer-generated test audio, it operates with an expected accuracy of 99.4% and a worst-case accuracy of 98.3%. This could almost certainly be improved with better algorithms. Many of the errors were around bad results from the exceedingly basic voice detection algorithm used.

Still, there is much room for improvement. First, many of the calls containing telephone metadata will be to the same destination numbers. The accuracy of number identification could be significantly improved by cataloging those destination numbers which ask users for telephone metadata and those that don't. In this way it would be trivial to categorize the great majority of calls as either potentially containing telephone metadata or not containing telephone metadata.

We can also improve how accurately we can determine if tones consist of a phone number or not. Where the existing CCAD implementation examines only the number of digits, we could also measure the time between digits. Humans tend to remember (and therefore dial) numbers in small groups. We even write the numbers this way. For example, credit card numbers are written as four groups of four, while domestic phone numbers are written in groups of three, then three, then four digits. Humans memorize numbers in this format or, if looking at a written number, tend to read and dial one chunk, then read and dial the next. This means that the dialed digits will have longer pauses between them when switching between groups. In turn, this can be used to correlate a dialed sequence with a format and determine if the number dialed is a phone number.

Finally, the differentiation between telephone metadata and content could be even further improved by using voice transcription software to determine what information the user is being asked for.

How Did FISCR get it Wrong?

From the legal side, CCAD operates as a sort of “taint team”. In many digital search situations, it is difficult to perform a search for specific information without also having to examine information that is outside the scope of a warrant. In this situation, a taint team is used. The team is given a list of terms or other filter assembled by the investigators and approved as part of the warrant. They then examine the entire body of digital information and isolate any that should be returned under the warrant.

CCAD takes this one step further. Rather than have humans go through and isolate phone numbers, software (which cannot chose to hold on to or leak information) does the task. It ensures that no information the intelligence agencies are not entitled to is collected, stored or even seen (or heard) by a human.

At a minimum, the court should have ordered the use of a minimization procedure similar to CCAD and denied the intelligence agencies permission to store calls. Put simply, they don't need to store them or keep any information other than the symbolic representation of the dialed tones. Any additional information they keep is overreach and violates the fourth amendment.

CCAD proves, using only technology older than me, that separating dialed tones from a call and determining if they are telephone metadata is not only a reasonable thing to do, but can be done in better than real-time. It is further worth noting that I wrote this in six weeks of nights and weekends. While I'm a competent developer, digital signals processing is not an area where I have any education and I spent a lot of time educating myself.

This raises an important question: If I, a computer scientist with no background in digital signals processing or telephony software, can throw together a solution in a month, why did the court find that it was impossible? The most charitable interpretation of this is a simple miscommunication somewhere between the technical experts and the court. However, it stretches credibility to believe that this is the case. Despite having at least three people to go through, it seems unlikely that even “it's hard” would morph into “it's impossible”. (And this certainly isn't a hard problem).

The next option is a deliberate, deceptive truth. This seems more the style of our intelligence agencies. In the past, we've seen the NSA tell congress things that are technically true (“We don't do that type of monitoring under that section of law”) but which are intended to imply something different than the truth (for example, to imply that the NSA doesn't collect that data). If we had access to the transcript for this case, this deception might take the form:

JUDGE: So you're saying you cannot tell the difference between digits dialed as telephone metadata and those that are content?

GOVERNMENT: No. There is no technical difference between a digit dialed as part of a phone number and one dialed as part of the content.

While the government's answer to this question looks straightforward, it's actually answering a slightly different question. Rather than answering if the government can differentiate the purpose of multiple digits, it answers if the government can determine the purpose of a single digit in isolation. It's a very subtle difference, but in this context a critical one.

I don't know and will likely never know what happened. I'd like to believe the miscommunication theory because I hope the representatives of our intelligence agencies do not feel the need to dissemble to the courts to get what they want. However, given past behavior, (such as spying on and deleting documents from the computers of their oversight committee) the intelligence agencies have not earned enough trust for me to automatically and wholeheartedly believe the charitable interpretation.

FISA's Independence and Efficacy Must be Questioned

No matter the reason, the efficacy and independence of the FISA courts is called into question. The court made a finding based on bad “facts” that a simple consultation with independent technical experts would have conclusively disproved (without even having to reveal anything classified). The court made legal missteps at every turn, contradicting the Supreme Court, failing to require minimization procedures as required by law and allowing the collection and storage of protected fourth amendment information without appropriate due process or warrants.

Worse, it appears the protections put in place by the FISA Amendment Act of 2008 are not performing their intended purpose. This act required an amicus – friend of the court – to argue against the government. In this case that role was filled by Marc Zwillinger, an extremely prominent privacy lawyer. Despite being among the very best in his field and extremely well prepared to argue the effects this decision will have, the court appears to have more or less ignored him. In fact, at points it appears to even treat his suggestions with derision, fixating on a portion of an argument without examining it in context and therefore allowing it to treat all his arguments as irrelevant. It is telling that the decision focuses almost exclusively on the government's arguments and gives only token attention to Mr. Zwillinger's.

This appears to be how most of these cases go. FISC, the lower court, received 1457 applications for electronic surveillance in 2015. (These are not broken down by type in the publicly available information, but include both warrants and pen register applications). FISC denied precisely zero of these. Some were likely pen registers which, as we've seen cannot be denied. FISC modified only 80 applications – about 5.5%. Even if we're being generous and counting modification as disagreement with the government, FISC granted everything the government asked for almost 95% of the time. Frankly this doesn't look to me like anything other than token oversight.

Combine that with the court so obviously bowing to what the government wants in this case and the FISA courts begin to look like kangaroo courts. They lend a veneer of legitimacy to the operations of the intelligence agencies. But that is all it is, a veneer that falls apart under any real independent scrutiny.

In addition to reversing this clearly-faulty decision, it is clear that the paradigm under which the FISA courts operate needs to be reexamined.

FISCR and The Bill of Rights

Finally, we need to discuss the fourth amendment. It is written very specifically to prevent government interference in the lives of citizens without showing a good reason. And for a good reason too. Before the Revolutionary War, King George's troops would arbitrarily search the homes of those who disagreed with them. It was a form of harassment, designed to deter disagreement. So when the time to draft the Constitution came, the founding fathers wrote the fourth amendment to prevent searches being used to harass citizens.

The theory that government intrusion, even if it does not result in prosecution or any consequences, can be used as a tool to suppress dissent is called the "chilling effect". Applied here, the chilling effect means that citizens, knowing they could be spied on at any time, will avoid expressing anti-government opinions.

This is the fundamental tool of repressive governments. It has no place in the United States and goes against our fundamental values.

Conclusion

FICOR's decision is unamerican. It contradicts both the text and intent of the fourth amendment. It opens the door to massive government intrusion into private life, in much the same way as the violations that lead to the Revolutionary War. It must be opposed, lest we as Americans lose our fundamental freedoms and lose the values of our nation.

This is why we are opposing it.

I will continue to post updates here as the case develops. For questions or comments, contact me.